Understanding the stress response

Chronic activation of this survival mechanism impairs health

A stressful situation — whether something environmental, such as a looming work deadline, or psychological, such as persistent worry about losing a job — can trigger a cascade of stress hormones that produce well-orchestrated physiological changes. A stressful incident can make the heart pound and breathing quicken. Muscles tense and beads of sweat appear.

This combination of reactions to stress is also known as the “fight-or-flight” response because it evolved as a survival mechanism, enabling people and other mammals to react quickly to life-threatening situations. The carefully orchestrated yet near-instantaneous sequence of hormonal changes and physiological responses helps someone to fight the threat off or flee to safety. Unfortunately, the body can also overreact to stressors that are not life-threatening, such as traffic jams, work pressure, and family difficulties.

Over the years, researchers have learned not only how and why these reactions occur, but have also gained insight into the long-term effects chronic stress has on physical and psychological health. Over time, repeated activation of the stress response takes a toll on the body. Research suggests that chronic stress contributes to high blood pressure, promotes the formation of artery-clogging deposits, and causes brain changes that may contribute to anxiety, depression, and addiction. More preliminary research suggests that chronic stress may also contribute to obesity, both through direct mechanisms (causing people to eat more) or indirectly (decreasing sleep and exercise).

Sounding the alarm

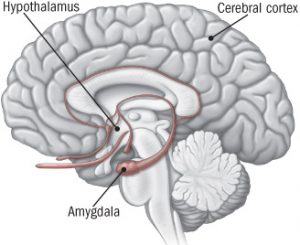

The stress response begins in the brain (see illustration). When someone confronts an oncoming car or other danger, the eyes or ears (or both) send the information to the amygdala, an area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing. The amygdala interprets the images and sounds. When it perceives danger, it instantly sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus.

Command center

illustration of brain showing areas activated by stress

When someone experiences a stressful event, the amygdala, an area of the brain that contributes to emotional processing, sends a distress signal to the hypothalamus. This area of the brain functions like a command center, communicating with the rest of the body through the nervous system so that the person has the energy to fight or flee.

The hypothalamus is a bit like a command center. This area of the brain communicates with the rest of the body through the autonomic nervous system, which controls such involuntary body functions as breathing, blood pressure, heartbeat, and the dilation or constriction of key blood vessels and small airways in the lungs called bronchioles. The autonomic nervous system has two components, the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system functions like a gas pedal in a car. It triggers the fight-or-flight response, providing the body with a burst of energy so that it can respond to perceived dangers. The parasympathetic nervous system acts like a brake. It promotes the “rest and digest” response that calms the body down after the danger has passed.

After the amygdala sends a distress signal, the hypothalamus activates the sympathetic nervous system by sending signals through the autonomic nerves to the adrenal glands. These glands respond by pumping the hormone epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) into the bloodstream. As epinephrine circulates through the body, it brings on a number of physiological changes. The heart beats faster than normal, pushing blood to the muscles, heart, and other vital organs. Pulse rate and blood pressure go up. The person undergoing these changes also starts to breathe more rapidly. Small airways in the lungs open wide. This way, the lungs can take in as much oxygen as possible with each breath. Extra oxygen is sent to the brain, increasing alertness. Sight, hearing, and other senses become sharper. Meanwhile, epinephrine triggers the release of blood sugar (glucose) and fats from temporary storage sites in the body. These nutrients flood into the bloodstream, supplying energy to all parts of the body.

All of these changes happen so quickly that people aren’t aware of them. In fact, the wiring is so efficient that the amygdala and hypothalamus start this cascade even before the brain’s visual centers have had a chance to fully process what is happening. That’s why people are able to jump out of the path of an oncoming car even before they think about what they are doing.

As the initial surge of epinephrine subsides, the hypothalamus activates the second component of the stress response system — known as the HPA axis. This network consists of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands.

The HPA axis relies on a series of hormonal signals to keep the sympathetic nervous system — the “gas pedal” — pressed down. If the brain continues to perceive something as dangerous, the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which travels to the pituitary gland, triggering the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This hormone travels to the adrenal glands, prompting them to release cortisol. The body thus stays revved up and on high alert. When the threat passes, cortisol levels fall. The parasympathetic nervous system — the “brake” — then dampens the stress response.

Techniques to counter chronic stress

Many people are unable to find a way to put the brakes on stress. Chronic low-level stress keeps the HPA axis activated, much like a motor that is idling too high for too long. After a while, this has an effect on the body that contributes to the health problems associated with chronic stress.

Persistent epinephrine surges can damage blood vessels and arteries, increasing blood pressure and raising risk of heart attacks or strokes. Elevated cortisol levels create physiological changes that help to replenish the body’s energy stores that are depleted during the stress response. But they inadvertently contribute to the buildup of fat tissue and to weight gain. For example, cortisol increases appetite, so that people will want to eat more to obtain extra energy. It also increases storage of unused nutrients as fat.

Fortunately, people can learn techniques to counter the stress response.

Relaxation response. Dr. Herbert Benson, director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, has devoted much of his career to learning how people can counter the stress response by using a combination of approaches that elicit the relaxation response. These include deep abdominal breathing, focus on a soothing word (such as peace or calm), visualization of tranquil scenes, repetitive prayer, yoga, and tai chi.

Most of the research using objective measures to evaluate how effective the relaxation response is at countering chronic stress have been conducted in people with hypertension and other forms of heart disease. Those results suggest the technique may be worth trying — although for most people it is not a cure-all. For example, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital conducted a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of 122 patients with hypertension, ages 55 and older, in which half were assigned to relaxation response training and the other half to a control group that received information about blood pressure control. After eight weeks, 34 of the people who practiced the relaxation response — a little more than half — had achieved a systolic blood pressure reduction of more than 5 mm Hg, and were therefore eligible for the next phase of the study, in which they could reduce levels of blood pressure medication they were taking. During that second phase, 50% were able to eliminate at least one blood pressure medication — significantly more than in the control group, where only 19% eliminated their medication.

Physical activity. People can use exercise to stifle the buildup of stress in several ways. Exercise, such as taking a brisk walk shortly after feeling stressed, not only deepens breathing but also helps relieve muscle tension. Movement therapies such as yoga, tai chi, and qi gong combine fluid movements with deep breathing and mental focus, all of which can induce calm.

Social support. Confidants, friends, acquaintances, co-workers, relatives, spouses, and companions all provide a life-enhancing social net — and may increase longevity. It’s not clear why, but the buffering theory holds that people who enjoy close relationships with family and friends receive emotional support that indirectly helps to sustain them at times of chronic stress and crisis.